Bee Thankful This Season

- 2019-11-06

- By danibash

- Posted in The Garden Buzz

By Lisa Mason, Horticulture Agent

Since you know by now that this is my favorite topic, I couldn’t let the holiday season pass by without praising pollinators!

We have so much to be thankful for this holiday season including the meals we eat. Have you ever wondered how much of the food is on our tables for which we can thank pollinators? Approximately 1/3 of our diet is dependent on pollinators, including some of our most nutritious fruits, vegetables, and nuts. Even our meat and dairy industries depend on pollinators because bees pollinate alfalfa and clover, which are food sources for cattle. (Food staples like corn, rice, soybeans, and wheat are either wind-pollinated or self-pollinated.)

Honey Bee

Native Bee

Both native bees and honey bees provide valuable crop pollination services.

Photo Credit: Lisa Mason

As you plan your holiday meals with family and friends, we can think about all the delicious foods we have because of pollinators. Here is a list of common food items and who pollinates them provided by The Pollinator Partnership:

- Almonds – Honey bees

- Anise – Honey bees

- Apples – Honey bees, blue mason orchard bees

- Apricot – Bees

- Avocado – Bees, flies, bats

- Blueberry: Over 115 kinds of bees, including bumblebees, mason bees, mining bees and leafcutter bees

- Cardamom – Honey bees, solitary bees

- Cashew: Bees, moths, fruit bats

- Cherry: Honey bees, Bumblebees, Solitary bees, flies

- Chocolate – Bees, flies

- Coconut – Insects, fruit bats

- Coffee – Stingless bees, other bees, flies

- Coriander: honey bees, solitary bees

- Cranberries – Over 40 bee species

- Dairy – Dairy cows eat alfalfa pollinated by leaf cutter and honey bees

- Fig – Over 800 species of fig wasps

- Grape – Bees

- Grapefruit – Bees

- Kiwi fruit: Honey bees, bumblebees, solitary bees

- Macadamia nuts: Bees, beetles, wasps

- Mango: Bees, flies, wasps

- Melon: Bees

- Nutmeg – Honey bees, birds

- Peach: Bees

- Pear: Honey bees, flies, mason bees

- Peppers: Bumble bees

- Peppermint – Bees, flies

- Pumpkin – Squash and gourd bees, bumble bees

- Raspberry and Blackberry: Bees, flies

- Strawberry: Bees

- Sugar cane – Bees, thrips

- Tea plants: Flies, bees, and other insects

- Tomato: Bumble bees

- Vanilla – Bees

Note: This list is not comprehensive. Many other crops also require pollination by insects and animals.

Where Do Bees Go in the Winter?

I have been asked a few times this season what happens to the bees in the winter. Bees and other insects have special adaptations, so their species survives from year to year. Here is a look at bee adaptations.

Honey Bees

Worker bees foraged all summer and into fall bringing in food reserves to last them the winter. When temperatures start to drop, honey bees huddle together to make a cluster and shiver their wings. Shivering provides warmth for the hive. Their main goal is to keep the queen warm so the colony can survive. The core temperature in the hive can be as high as approximately 91 degrees Fahrenheit. A healthy hive with adequate food storage is more likely to survive, which reinforces the importance of best beekeeping practices by the beekeeper all year. Read how to prep a hive for winter here.

Solitary Bees

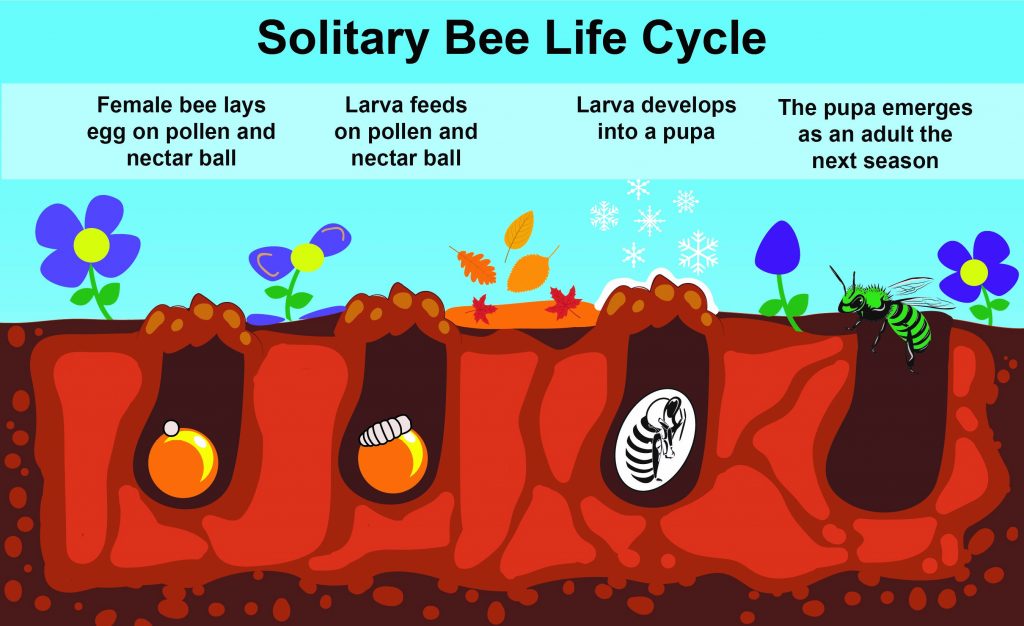

Solitary bees live a one-year life cycle. During the life cycle, a female bee builds a nest underground or in a cavity. She will collect pollen and nectar to bring back to the nest. All the collected pollen and nectar is made into a ball called “bee bread” which will be all the food needed for one growing bee. The female lays an egg on the bee bread and seals up the nest. After the egg hatches, the larva will go through full metamorphosis from a larva, to a pupa, and on to an adult before emerging from the nest the following season. The lives ended for the female and male solitary bees we saw flying around this summer, but their brood is warm for the winter and will emerge next summer.

Bumble Bees

Bumble bees live underground or in large cavities and have a one-year life cycle, like a solitary bee. During the summer, new queens and male bees hatched. They left their colonies to mate. As temperatures dropped, the male bees and worker bees from the current season’s colony died. The new, mated queens found a place to rest and hibernate over the winter, usually underground. When spring arrives, she will emerge, begin to forage, build a new nest, and lay eggs. The eggs will mostly be female worker bees at the beginning of the season. The queen will continue to lay eggs throughout the season. In late summer, new queens and male bumble bees will hatch and leave the colony and the cycle repeats itself. Queen bumble bees are capable of living alone, unlike honey bee queens.

For more information on bee lifecycles, you can read the Native Bee Watch Citizen Science Field Guide.

For more information on what happens to other insects in the winter, you can refer to this CO-Horts Blog post written by Jessica Wong.